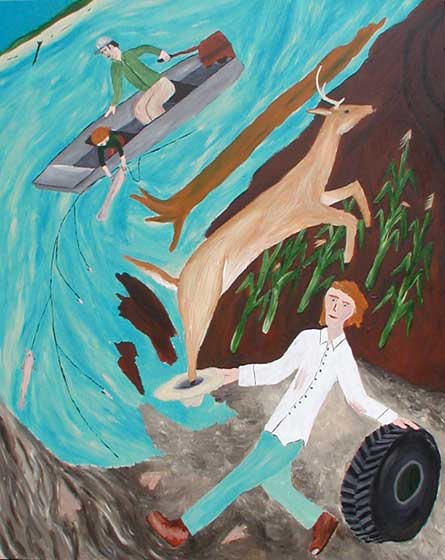

“Deer Hat and Trotline” contemporary figurative painting. acrylic on wood. 24 in x 30 in.

“Deer Hat and Trotline” contemporary figurative painting

When I was about six years old, my father started taking me with him out into the River to run trotlines in the backwaters. The trotline were made out of nylon cord, and there were about 50 to a 100 hooks one-inch spaced about every two feet. We baited the hooks with chunks of freezer-burnt deer meat or spoiled meat that we got from grocery store for free. You tied one the end of line to a tree, left it overnight and came back the next day to work the line. Mostly we caught catfish in the range of five to twelve pounds, although 30 pounds and up was possible and sometimes huge gar.

The first time Daddy took me, he worked the line. He pulled the catfish off the line and let them flop in the bottom of the johnboat. They weighed almost as much as I did, so I kept my distance. I was watching them gasp for air when Daddy pulled a fresh one in that still had a lot of fight left. All of a sudden, he slapped the side of the boat with his tail, and then they all started flopping and slapping, and it was as loud and as violent as a fist fight. I guess I jumped out of the boat to get away from it all because the next thing I remember was Daddy pulling me up by the back of my life jacket and throwing me into the bottom of the johnboat like a fish. He only had one free hand because he had to keep one hand on the trotline or the current would carry us away. I’m sure he said something like, “Boy, stay in the boat.” And then he kept working the trotline without saying anything else about it.

Once we were running a trotline and the River had risen suddenly and unexpectedly due to heavy rains up north. That meant there was a lot more current in the backwater than when we put the line out. I remember the water looked angry and boiling like out in the main channel. The current was pulling strong, so Daddy had to keep the nylon cord wrapped around his hand as he pulled us up the trotline. Suddenly a sunken tree floated by and hit the trotline about 30 yards from the boat and snatched the line out of his hand. One of the one-inch hooks caught him and went through the palm of his hand. (Clean through, like Jesus.) The line pulled him to the back of the boat in an instant and slammed him against the outboard motor. He wrapped the line around his other arm in one quick motion and said, “Boy, get me the needle-nose pliers out of the tool box.”

Of course I panicked and brought him the wrong thing, but when he finally got the wire cutters, he cut the barb off the end of the hook and pushed at back through and let the line go. Then he cussed for a minute about the floating tree and losing the trotline, and then he got some orange Mercurichrome (iodine) out of the toolbox, squirted it all over his hand and then went back to start the outboard motor.

He squeezed the bulb on the fuel line and pulled the cord on the motor. He pulled once, twice, then five more times, but it wouldn’t start. He waited, then pulled the cord a few more times, squeezed the bulb again, then pulled the cord again. He pulled the cord over and over, and it wouldn’t start. Just coughing blue smoke that smelled like gasoline and outboard oil. He pulled until the motor was clear of fuel and then pumped the bulb and pulled some more. By now it was getting late and the sky was starting to get a little dark. He cussed under his breath. “Be done floated past the Greenville bridge fore this son of a bitch comes to.”

He had me slide him the tool box, and then he took the cowling off the motor and messed with it as he cussed. Then he pulled the cord some more, but it wouldn’t start. Then the recoil on the pull cord sprung, and the cord wouldn’t recoil anymore. Then he started to cuss in earnest. He cussed the motor, the trotline, the floating tree, my momma bitching when we got home, the new Japanese cars, government subsidies to “bigtime” farmers, welfare, lawyers, the politicians in Washington, etc.

Then he paddled us over to a sandbar and had me hold the flashlight as he flushed out the fuel line and put everything back together. It was pitch dark when we got back to the truck and pulled the boat out.

Of course my father never went to the doctor or anything for the hook. That was a clean in-and-out puncture wound, which was nothing compared to the gouges and gashes he saw everyday as a pipeline welder. His hands always had orange Mercurichrome stains on them. Besides, Daddy grew up tenant farming with my great grandfather’s family in the Delta, and I think his attitudes about what constitutes a medical emergency are a little different than most people’s.

The other half of the painting is about my 13 great uncles, most of whom lived up in the hills southeast of Oxford. We would see them when we would go up there deer hunting in the fall. They told me stories about what it was like working all day long and what it was like before the TVA brought electric lights down into Mississippi, and how they had never tasted a banana and all that sort of stuff. They walked the creeks with me and showed me how to find arrow heads and petrified wood.